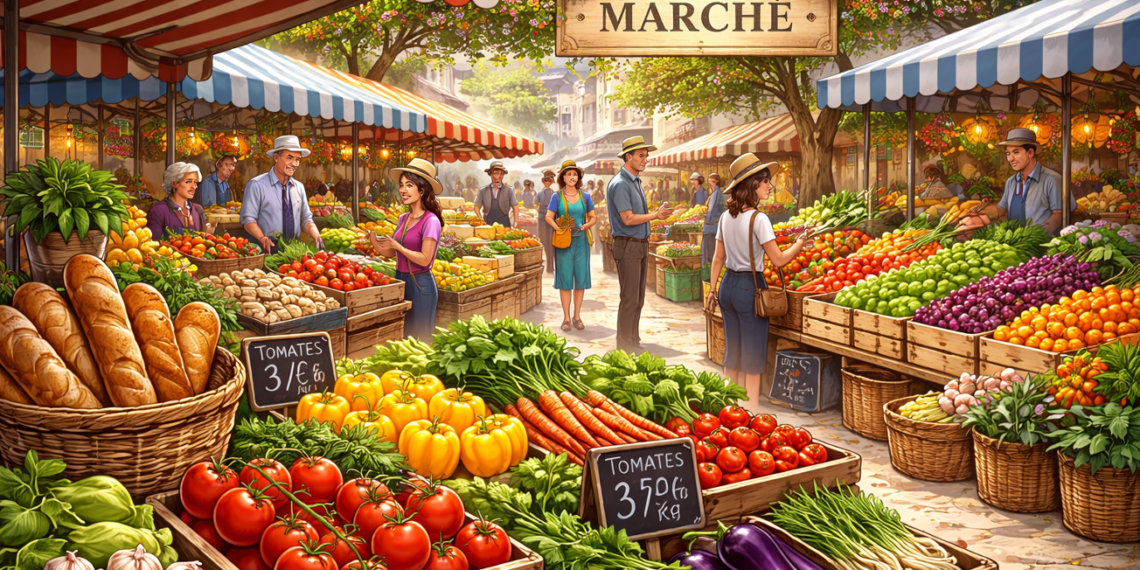

Before the kitchen gets warm. Before the knife touches the board. Before the recipe is even consulted, there is another place. A louder, brighter, more colourful place. This is where French cooking truly begins.

The marché—the open-air market—is not simply a place to buy food. It is where decisions are made. It is where the meal takes its first breath. In France, what you cook for dinner often depends entirely on what looks best that morning, not on what you scribbled on a list the night before. The market does not just supply the meal. It shapes it. It whispers to you, Today, this. Today, not that.

Most towns hold their market once or twice a week, a temporary festival of food that springs up in the central square. Larger cities have their halles, permanent covered markets that hum with daily purpose. But wherever it is, you must go early. In the first hours, the light is soft and the air is cool. The atmosphere is calm, but it is a purposeful calm. People walk slowly, their baskets swinging, their eyes scanning. They stop. They look closely. They ask questions.

Buying is almost secondary. Choosing well is everything.

Buying by Season, Not by List

At the marché, food appears when nature intends it. The strawberries arrive in late spring, fragrant and fragile, here for a moment and then gone. The mushrooms emerge in autumn, earthy and dark. The asparagus has its brief, glorious few weeks. Because of this, French home cooking develops a rhythm that feels almost like breathing.

You cook the same vegetable over and over while it is perfect. You roast it, you steam it, you eat it raw with a drizzle of good oil. And then, when the season fades, you simply stop. You do not search for an import from halfway across the world. You wait. The absence becomes part of the pleasure.

This rhythm simplifies everything. Instead of forcing variety by chasing different ingredients, the cook varies the technique. The ingredient stays the same; the method changes. The market teaches a deep, patient truth: variety comes from time, not from importing everything all year.

The vendors are your guides in this. You can stand before a pile of tomatoes and ask, “Are these ready for tonight?” And they will give you an honest answer. Eat these now, they are sweet. These others need two more days on the windowsill. These are better for cooking into a sauce. Over weeks and months, trust builds. Regular customers do not poke and prod at the produce; they simply ask, and rely on the answer. It is a relationship.

The Specialist Stalls

A supermarket lumps everything together. The marché is different. It separates food by expertise, by craft. Each stall is a small kingdom of knowledge.

- The fromager presides over a landscape of cheese. They will discuss ripeness, cut you a slice from the very heart of the wheel, and tell you exactly when to serve it.

- The poissonnier, with their gleaming display of the morning’s catch, will suggest a simple grill for the firm fish, or a quick en papillote for the delicate one.

- The boucher, wielding his knife with surgical precision, knows which cut needs hours of slow braising and which can be in and out of the pan in minutes.

- The maraîcher, the vegetable grower, their hands still dusty with soil, can tell you exactly where those carrots were grown, and how.

Because each seller knows their product so deeply, the recipes become flexible. A short conversation can change your entire dinner plan. Advice, given freely and warmly, replaces the cold instructions on a package.

Conversation as Part of Cooking

The market moves at a human pace. It is not a rush. People greet each other. They exchange news. They ask the volailler how to cook that unfamiliar bird they just spotted. This chatter is not a distraction from the shopping. It is the shopping. It is culinary education, passed from hand to hand, mouth to mouth.

Over time, a regular market-goer learns. They learn how a rainy week affects the flavour of strawberries. They learn why the chèvre tastes different this month than it did last month. They learn when a fish is best eaten raw, and when it needs the confidence of a hot pan.

Children are always there, trailing behind adults, half-listening, half-wandering. They learn without knowing they are learning. They see the tomatoes disappear in winter, and they do not ask for them. They understand, deep in their bones, that some things are worth waiting for.

The Basket Becomes the Menu

At the end of the morning, the basket is full. And now, and only now, does the menu reveal itself.

That whole chicken, with its golden skin, is clearly asking to be roasted simply, with a clove of garlic and a sprig of thyme. The bunch of fresh herbs, still damp, suggests a sharp, green salad. The wedge of ripe cheese, soft and pungent, means you will not need dessert. The meal builds itself.

This is the reverse of how we often cook. We usually find a recipe, then shop for it. The French method, rooted in the marché, does the opposite. It cooks from observation. It lets the ingredients lead.

The Starting Point of Cuisine

The marché, in the end, represents the true starting point of French cuisine. It is not a detour on the way to the kitchen. It is the first, most essential step.

Cooking begins not with technique, but with attention. With looking. With asking. With choosing.

Choose well at the market, and the recipe becomes simple. The food almost knows what to do next.