Rajasthani cuisine is not merely a collection of dishes—it is a culinary chronicle of war, scarcity, and regal extravagance. Born from the arid deserts, fortified palaces, and the martial ethos of the Rajputs, this Royal Cuisine is a paradox of rustic ingenuity and royal decadence. Unlike the fertile plains of Punjab or the coastal abundance of Bengal, Rajasthan’s harsh terrain demanded resourcefulness—ingredients that could last months without spoiling. Techniques that maximized flavour from minimal produce, and a spice-laden palate designed to stimulate appetite in a land where fresh food was often a luxury.

A Cuisine Forged in War and Scarcity

The Rajput kings were warriors first, and rulers second. Their kitchens, or rasodas, were as strategic as their armories. Long sieges and frequent battles necessitated food that could sustain armies—grains that stored well, meats preserved in spices, and dairy transformed into long-lasting staples like ghee and khoa (reduced milk solids).

One of the most telling examples is Dal Baati Churma, a dish born out of necessity. Royal Cuisine includes warriors baking baati, the hard, unleavened wheat bread, directly in desert sands or over open flames, needing no utensils. It was carried by soldiers, crushed when needed, and paired with dal (lentils) for protein. The addition of churma—a sweetened, crumbled version of baati—provided quick energy, making it a complete wartime ration.

Similarly, Laal Maas, the fiery mutton curry, was a display of Rajput valour and a preservation technique. The heavy use of red chilies (originally Mathania chilies, indigenous to Rajasthan) acted as a natural preservative. Yoghurt tenderized tougher cuts of meat from desert-hardened goats.

The Royal Kitchens: Where Opulence Met Innovation

While commoners relied on frugality, the Rajput courts turned scarcity into a spectacle. The Maharaja’s khansamas (royal cooks) were masters of culinary alchemy, transforming simple ingredients into lavish feasts. This was the essence of Royal Cuisine.

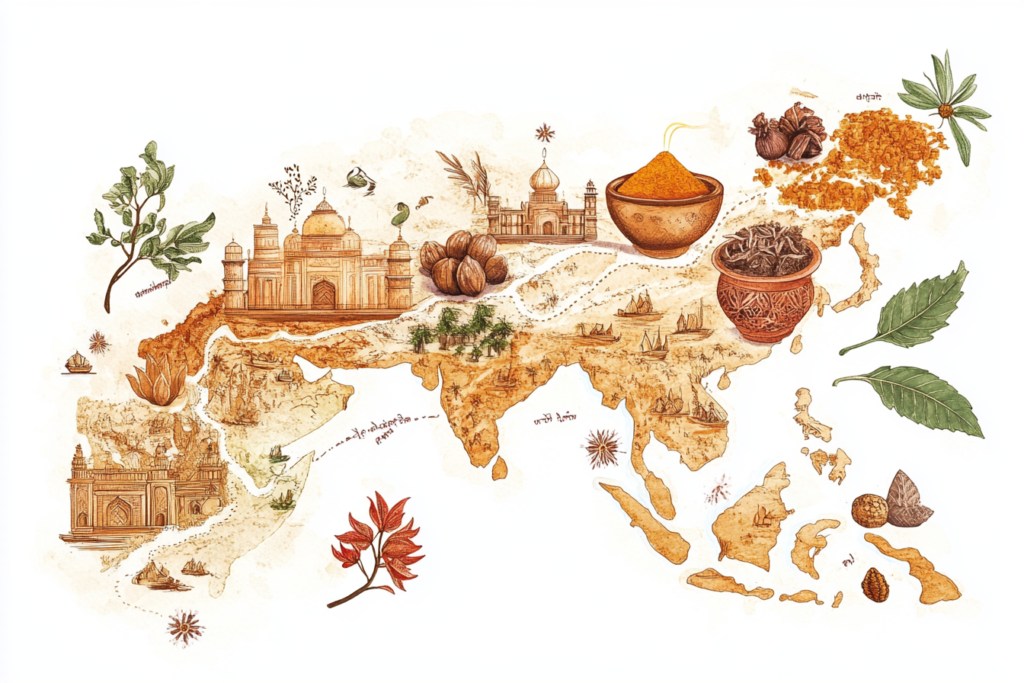

One such technique was Dum Pukht, slow-cooking in sealed pots. This allowed tough desert meats to become succulent. The royal version of Safed Maas (white meat curry) used cashew paste, cream, and aromatic spices like cardamom and saffron. These ingredients were sourced from trade routes that connected Rajasthan to Persia and Central Asia.

Another hallmark of Rajputana royalty was marination in buttermilk or yoghurt. This method not only tenderized game meats like wild boar and venison but also countered the dryness of desert-raised animals. Royal Cuisine dishes like Jungli Maas (hunter’s curry) and Khud Khargosh (hare cooked in a pit) were testaments to the hunting traditions of the nobility.

Marwari and Rajwadi Cuisine

While Rajput courts revelled in game and meat, the Marwari community—devout Jains and Vaishnav Hindus—crafted an entirely vegetarian repertoire that was no less rich. The absence of onion and garlic (considered too stimulating for ascetic practices) led to the use of asafoetida (hing), dried mango powder (amchur), and robust spice blends to compensate.

Gatte ki Subzi, for instance, replaced meat with gram flour dumplings. These were simmered in a spiced yoghurt gravy thickened with besan (chickpea flour). Ker Sangri, a desert speciality, used wild berries (ker) and beans (sangri) foraged from the arid landscape. They were cooked with mustard oil and spices to create a dish that could last weeks.

The influence of Mughlai cooking seeped in through dishes like Mohan Maas, a slow-cooked lamb in milk and saffron. Yet, Rajwadi cuisine retained its distinct identity with dishes like Bajre ki Raab (a warming millet porridge with ginger and jaggery) and Methi Bajra Puri (fenugreek-spiced millet bread). These exemplify the influence of Royal Cuisine.

The Sweets: A Legacy of Indulgence

No Rajput feast was complete without mithai, where the royal kitchens showcased their mastery over dairy and grains. Ghevar, a disc of honeycombed flour soaked in sugar syrup, was traditionally linked to Teej festivals. Its intricate texture was a testament to the skill of royal confectioners.

Moong Dal Halwa, a slow-stirred dessert of lentils, ghee, and sugar, was a winter speciality. Its richness designed to combat the desert chill. Mawa Kachori, deep-fried pastries stuffed with sweetened milk solids, reflected the Mughal-Rajput synthesis in desserts. Again, these are essential elements of Royal Cuisine.

The Techniques That Define Rajasthani Cooking

- Bhakri (Sand Baking): Before modern ovens, baatis were buried in hot sand or ashes. This method imparted a smoky depth.

- Sukhi Bhoj (Dry Cooking): Water was scarce, so many dishes, like Ker Sangri or Papad ki Sabzi, were cooked without gravy.

- Fermentation & Preservation: The use of kair (capers), sangri, and sun-dried lentils (papad, badis) ensured food security during droughts.

- Spice Infusions: Whole spices were often fried in ghee (tadka) and then removed. This left aroma without texture—seen in dishes like Rajasthani Kadhi.

A Living Tradition Under Threat

Today, the rasodas of old are fading. Industrialization has replaced Mathania chilies with generic varieties, and traditional bajra (millet) is losing ground to wheat. Yet, efforts by heritage chefs and food historians are reviving these recipes. They are documenting the exact spice ratios of Laal Maas, reinstating heirloom grains, and preserving techniques like sand-roasting that are crucial to Royal Cuisine.

Rajasthani cuisine is more than food—it is the story of a people who turned adversity into art, scarcity into splendor. To taste it is to taste history itself: fierce, resilient, and unapologetically regal. This is the essence of Royal Cuisine.